Why Cuban artists are leading the political revolt in their country

The artists are fighting for a population rendered ever poorer by Donald Trump's blockades and the decline of tourism during the pandemic

To some, she is known as a model who posed nude for Lucian Freud when he was 50 years her senior; to others, she is a trustee of the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, one of the most generous arts foundations in Britain. But Flora Fairbairn would rather be seen as an independent arts curator dedicated to discovering talent, and next week, she launches her eponymous consultancy with an exhibition of recent art from Cuba, which carries the evocative title The Weight of an Island in the Love of the People.

Having come from a family of artists, her journey in the art world changed direction when Freud told her she would make a good art dealer. Fairbairn had met him in 2000 after he saw her in a restaurant and tracked her down. He was a renowned womaniser, but, she says, “I never slept with him”. Yet the experience did sharpen her understanding of the creative process. She was also in close touch with an old school friend, Philippa Adams, who was working for Charles Saatchi as a curator, and the late African-art collector Robert Loder, a mentor with global contacts. Soon she was arranging exhibitions in temporary British locations, such as an empty floor in the Trellick Tower near Ladbroke Grove in west London.

Fairbairn first went to Cuba in 2009 on behalf of M&C Saatchi and the rum producer Havana Club International, to arrange an exhibition of local artists that could travel abroad. Although she loved the place, the logistics were hard to marshal. The artists’ work was censored; she felt that she was being constantly watched by someone who reminded her of Inspector Clouseau in The Pink Panther; and arranging transport and sending images for promotion worldwide was a nightmare with virtually no internet available.

Today, Fairbairn is building on her experience in Cuba with the help of a local curator, Sachie Hernández, to put together a second Cuban show. Together they have assembled work by 15 artists from different generations for an online exhibition of Cuban art, which goes live from next Monday on Fairbairn’s website, florafairbairn.com.

The exhibition comes at a time when artists are leading both political dissent and efforts to help a population rendered ever poorer by Donald Trump’s blockades and the emasculation of the tourism industry during the pandemic. “The situation there is electrifying,” says Fairbairn, “with Cuban artists demonstrating outside the Ministry of Culture, and Miami-based Cuban rappers taking on the government.”

The 52-year-old Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, for instance, whose installation in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2018 highlighted the plight of Syrian refugees, has been jailed several times for opposing the Communist regime. Last month, The Art Newspaper reported how artists had asked for their work to be covered up or taken off display in the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana as a protest against the forcible hospitalisation of Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, another performance artist, who had been on hunger strike in protest against the Cuban government’s clampdown on artists’ rights.

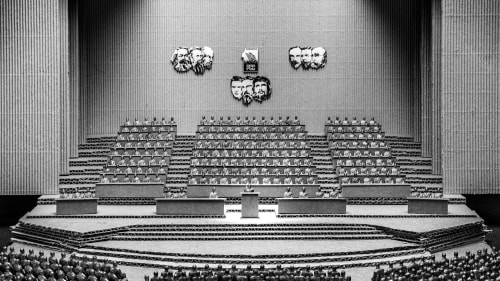

None of the artists in Fairbairn’s exhibition runs quite such risks, but they are acutely aware of the political issues. Digital photographs made in 2015 by Alejandro González recreate the Sovietisation of the Cuban economy and culture in the Seventies, with a performance of Swan Lake in the newly named Lenin Park and the first Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba at the Karl Marx Theatre. Behind the pulsing abstractions of Diango Hernández, there appear to be parallel references to biomorphic organisms and the movement of the sea that surrounds an island that has witnessed constant migratory movements over the centuries.

Juan-Miguel Pozo is a figurative artist who left Havana for Berlin in 1995, not to return for 20 years. His surreal renditions of Soviet realist art are a kind of subversion of the political propaganda he grew up with. His 2018 painting Zona Restringida shows two healthy blond schoolboys walking happily in a slightly arid, futuristic industrial landscape. Is this Utopia or a prison?

It’s a pity that The Weight of an Island in the Love of the People is not a physical exhibition, but the cost of shipping related to the price of the art (from a relatively modest £820 up to £17,620) makes it uneconomical. Meanwhile, 10 per cent of any profits will be going to Akokán, a project that seeks to improve the lives of Afro-Cubans living in dire socioeconomic conditions – which is a typically philanthropic Fairbairn gesture.